Who’s Responsible for Student Data: Data Controller Confusion in EdTech

In Spotlight Report #4, we introduced the problem of “data controller confusion” as it relates to EdTech. As we continue to process the findings from our 2022 US K12 EdTech benchmark data, we again see confusion over who is considered the responsible data controller when it comes to EdTech: is it the EdTech platform manufacturer or the Local Educational Agency (LEA) who licenses the technology? In particular, we are seeing a dearth of technology notice, consent and vetting practices in place in schools in the US. Detailed findings will be released soon. In this post, we share observations about EdTech distribution and data controller responsibilities when it comes to student data. Note that our goal is to highlight a public policy issue that needs greater scrutiny, we’re not trying to offer legal advice.

Technology Use Patterns in Schools

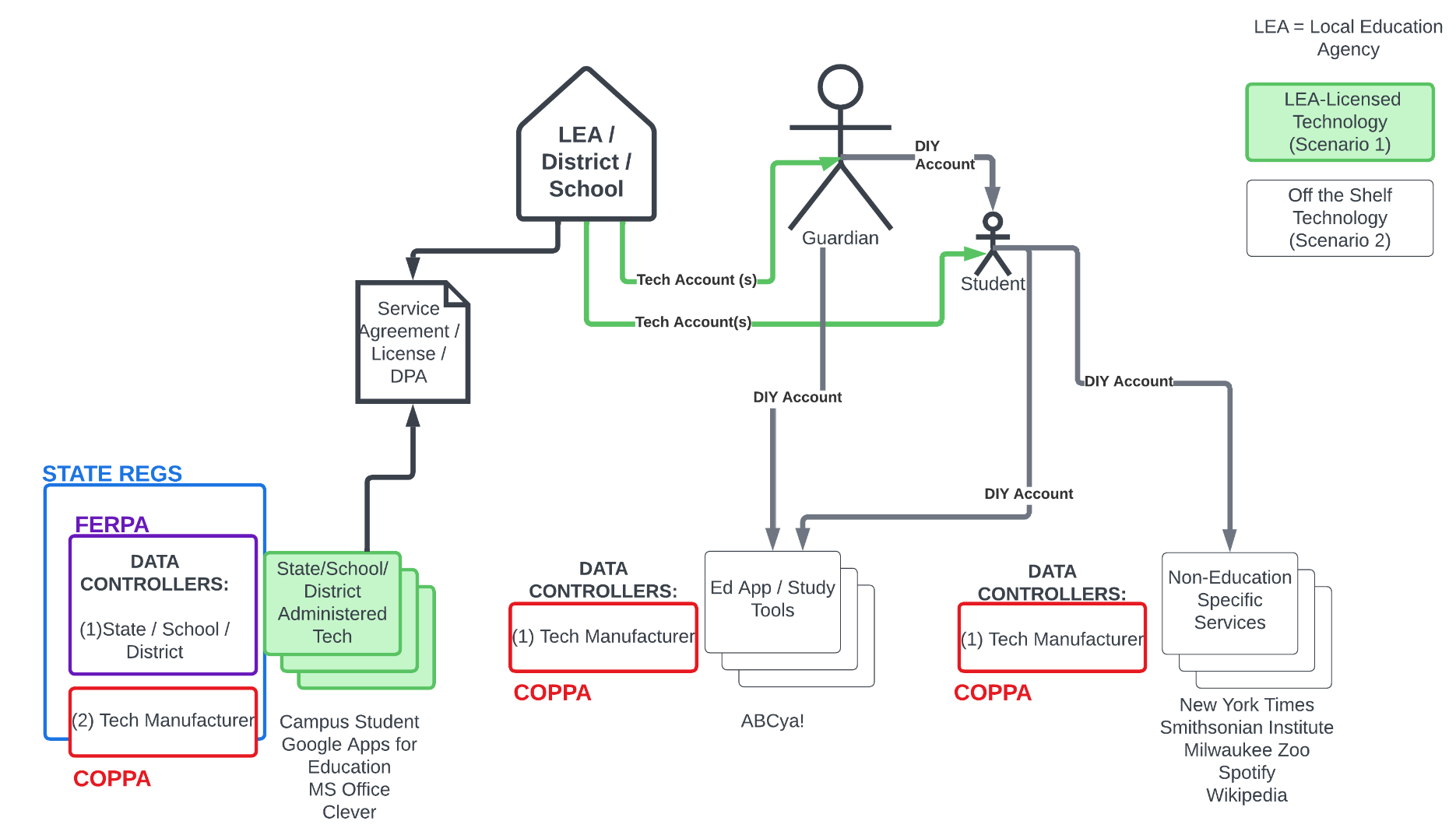

We find two main scenarios in K12 schools in the US. Technology used by students (recommended or required by the school) is usually either (1) licensed by the LEA, or (2) “off the shelf” technology where the LEA has no business relationship with the EdTech provider.

Scenario 1: LEA Licensed Technology

In the first scenario, there exists a legally binding agreement between the technology manufacturer and the LEA. Typically, the LEA is licensing the technology, with school or district branding/personalization, but likely without major functional customization. Technology providers create “white-labelled” versions of technology that can be readily re-skinned to reflect the LEA’s “brand(s)” (i.e. the school or district name).

In this scenario, user accounts for students et al are configured, provisioned, and administered by the LEA’s IT (Information Technology) personnel, using a dashboard control panel provided and maintained by the technology vendor.

Scenario 2: Off the Shelf Technology

In the second scenario, there is no business relationship between the LEA and the technology manufacturer. Students are referred to use technology and must procure it completely independently of the LEA. When students access technology off the shelf, parents may be required to confirm or indeed open and administer the account on behalf of the child. ABCYa! Games is one educational app that requires a parent to create an account.

Who’s the Data Controller?

LEAs and EdTech providers don’t currently seem to understand whether or not they are data controllers. We use the term “data controller” as defined by GDPR, the EU’s General Data Protection Regulation. GDPR and CCPA (California Consumer Privacy Act) are two important privacy regulations that govern privacy in technology including EdTech. The two regulations, however, differ to some extent on the terminology, definition, and scope of data controller.

From ISL’s perspective, an EdTech data controller (ala the GDPR data controller definition) is an EdTech entity that determines and controls the purposes and means of processing student data. Data processors, on the other hand, are defined in GDPR as a “a natural or legal person, public authority, agency or other body which processes personal data on behalf of the controller”. So an EdTech vendor likely engages one or more data processors to perform functions to support the EdTech service. For instance, an app may use Amazon Cloud Storage, which would then be a data processor.

Overlaying this definition onto the two scenarios described above clarifies the data controller roles.

Scenario 1: LEA Licensed Technology

In this scenario there are two data controllers; the LEA and the technology manufacturer both behave as data controllers and should be regarded as joint data controllers, a well-defined category under Article 26 in GDPR.

Both parties have a role in determining the purposes and means of processing student data.

The LEA typically administers the accounts and data, providing accounts to guardians, students, teachers, staff, and authorized third parties. The technology manufacturer has access to the school’s data and controls programmatic sharing of student data with integrated third-party software components (i.e. data processors or other joint data controllers). The LEA could never be construed as responsible for these programmatically embodied decisions made by the tech vendor. Thus, they are necessarily joint controllers.

But it’s still not totally clear: what about the case where there is a Data Privacy Agreement in place between the LEA and the tech vendor? In this case, could the LEA be said to be in control of the purposes and means of the student data processing?

Scenario 2: Off the Shelf Technology

In this scenario, there is no data controller confusion; the EdTech provider is the sole data controller. As noted earlier, there is no legally binding relationship between the LEA and the technology provider. The LEA does not have a role in the technology’s data collection, nor do they have access to the student data stored by the technology or the ability to share it. Note, however, that per COPPA, the school can—and, we observed, frequently does—consent on behalf of students. It’s unclear to ISL if or how this consent is provided back to and tracked by the tech providers.

Figure 1 below illustrates the various relationships between LEAs, tech providers, and students/guardians found in the two scenarios. Note that the diagram includes a third category of technology called “Non-Education Specific Services”, which are not education or child-specific technologies and include services such as online newspapers, Wikipedia, etc. We include these since they comprised 28% of the technology being recommended/required to US K12 students in our 2022 benchmark. The figure also shows the scope of relevant regulations.

In short, we suggest that the EdTech vendor always bears data controller responsibilities, either solely or jointly with the LEA, depending on the existence of business relationship between the two entities.

Figure 1