In our recently published research on the worldwide web of commercial surveillance, we took a close look at the global infrastructure connecting and correlating personal information across platforms, devices, and even from physical world sources like point-of-sales systems. The connectivity is, in a word, staggering. At some point, however, there is a first-party relationship with a data subject. From that starting point, personal information is systematically being shared with countless entities including data brokers. In such a hyper-interconnected infrastructure, how can a single publisher make promises about where customer data is going? Moreover, how could a user possibly consent to the sharing of their data with thousands of recipient organizations? But the complexity and unknowability of system behavior isn’t just with these hyper-interconnected marketing networks. As we touched on in a recent podcast with Zach Edwards, very large platforms (like Google, Facebook, X) are just as complex and opaque as the identity resolution and customer data platform networks. Software is increasingly a leaky, hyper-connected, unpredictable sieve of personal data sharing. In this blogpost, we take a closer look at the opacity and leakiness of the “big dogs”–large online platforms with hundreds of millions and billions of users.

1. Types of Commercial Identity Resolution

I’ve been digging into this more since the publication of our research on identity resolution and customer data platforms and have revised my framing of identity resolution. To wit, I observe three co-existing types of commercial identity resolution architectures or systems happening in the world:

- The first one I call distributed by design. This is the LiveRamps, The Trade Desks, mParticles, etc. of the world. These systems enjoy the power of massive data aggregation with [too] little of the risk and responsibility, as they are designed to be third-parties relative to the data subject. These platforms are architected to ingest and process (resolve) personal information from a disparate array of services and devices.

- The second one I call company-centric. This is the “big dog” platforms with millions or billions of users; the universes unto themselves. A company-centric identity resolution can also be distributed by design in the sense that it provides numerous small pieces of functionality which can be embedded as third-party resources into other companies’ apps and websites, allowing the big dogs to collect data external users despite not necessarily having direct relationships with them. Microsoft is a good example of this. It’s also true that company-centric identification schemes can and are ingested by distributed systems like LiveRamp. The lines implied by these two categories are fuzzy.

- The third one I call standardized. This is the hiding-in-plain-sight globally coordinated efforts in Unified ID 2.0 and European Unified ID. Note that these efforts are championed primarily by distributed by design identity resolution and customer data platforms. Scanning the partners of just the Unified ID 2.0 standard is enough to give one pause: these are the platforms that want to know who you are and what you’re doing at all times. Notably absent are the big dogs.

A brief word about national/governmental identification schemes, like India’s Aadhaar and the US Internal Revenue Service’s id.ME: these systems operate somewhat like a big dog company-centric identification system, orchestrating personal information across their own services, with the exception that we don’t expect these systems to be either ingesting or sharing data with external, commercial platforms1. At Internet Safety Labs (ISL), we rate “big dog” platforms as critical risk “data aggregators”2. We do so for the following two reasons:

- These corporate entities monetize personal information, either through ownership of advertising platforms, the selling of audience information, or other monetizing behaviors, and

- These entities run multiple consumer products and services with inadequate transparency of how personal information flows across product lines.

The remainder of this post takes a closer look at Google and Facebook (Meta) personal data strategies and why they’re so risky.

1.1 GAIA and Narnia: Google’s Universal Identification and Cross-Product Personal Data Aggregation Grand Plan

In the wake of the recent Google search antitrust case in the US, Jason Kint published a long thread on a recently unsealed 325-page Google strategy document. The document titled “Display, Video Ads, Analytics and Apps” contains a coordinated and synthesized set of business strategies describing how Google can:

- More effectively coordinate the extraction of user information,

- Better leverage user data across all of their AdTech, and

- In general, increase ad revenues across its entire portfolio of products and services: “make it easier to add monetization to other Google O&O [owned and operated] properties.”3

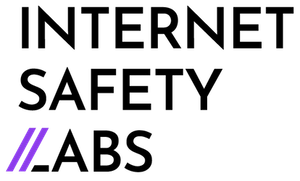

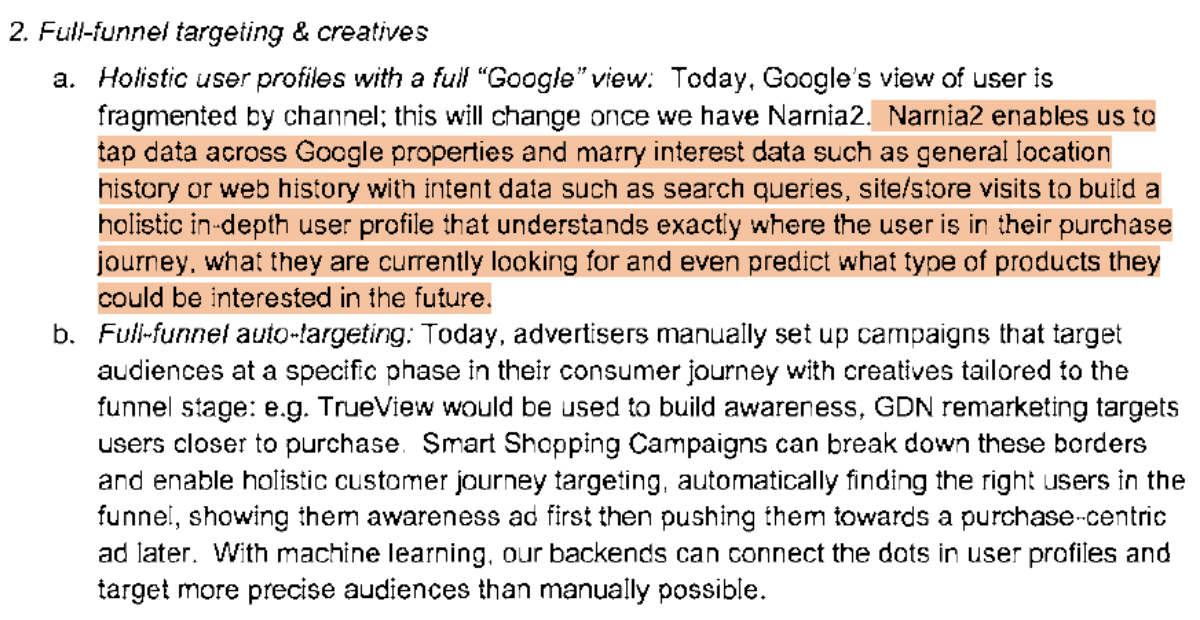

The document also covers how Google doesn’t make as much money from sites it doesn’t own and would like to assert its control to make them more like sites it does own, thereby increasing revenues. Nearly every product line’s strategy contained in the document mentions the use of “GAIA signals” or “GAIA data”. GAIA is Google’s proprietary “universal ID”4. The plan clearly outlines how they can better utilize the massive trove of personal information joined by their GAIA “universal IDs”, amassed across their various owned and operated (O&O) properties, like Gmail and Chrome to name two of the largest. This highlight from page 126 (section on “Smart Campaigns”) makes clear Google’s intention to share user information across all its properties to enrich their advertising services (project Narnia and Narnia2):  But it’s not enough to join user data across Google properties; they also indicate an intention to join external data sources, such as streaming and TV ad networks (pg 150):

But it’s not enough to join user data across Google properties; they also indicate an intention to join external data sources, such as streaming and TV ad networks (pg 150):  The second highlighted section above describes the ingesting of external customer data and resolving the data (i.e. identity resolution) to Google’s GAIA IDs. Overall, the document describes an organization-wide, orchestrated plan to amass and unify user data (via GAIA IDs) to better leverage Google ads (Narnia 2.0) for both internal and external properties. How can Google users understand–nevermind consent– to the use of their personal information in this wide-reaching way?

The second highlighted section above describes the ingesting of external customer data and resolving the data (i.e. identity resolution) to Google’s GAIA IDs. Overall, the document describes an organization-wide, orchestrated plan to amass and unify user data (via GAIA IDs) to better leverage Google ads (Narnia 2.0) for both internal and external properties. How can Google users understand–nevermind consent– to the use of their personal information in this wide-reaching way?

1.2 Facebook Admits Unknowability of User Data Processing

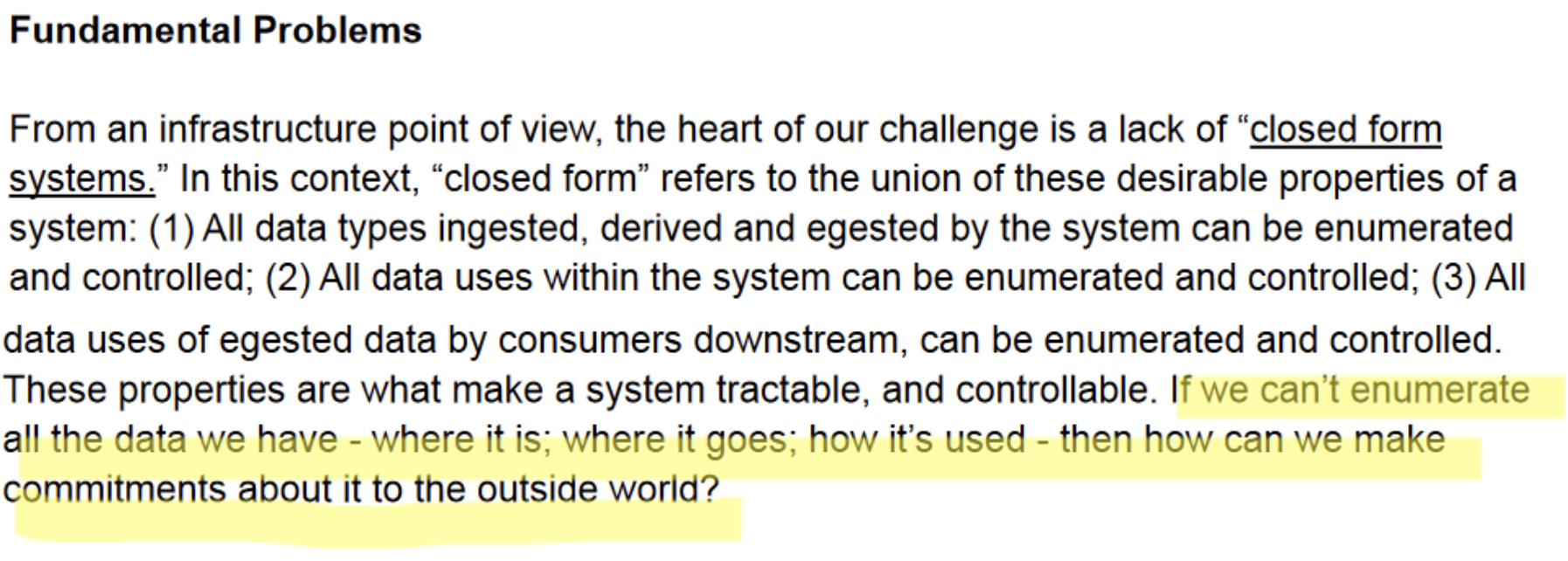

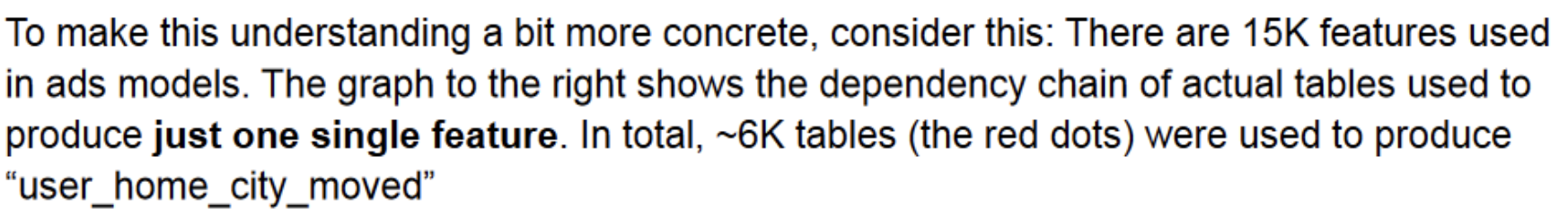

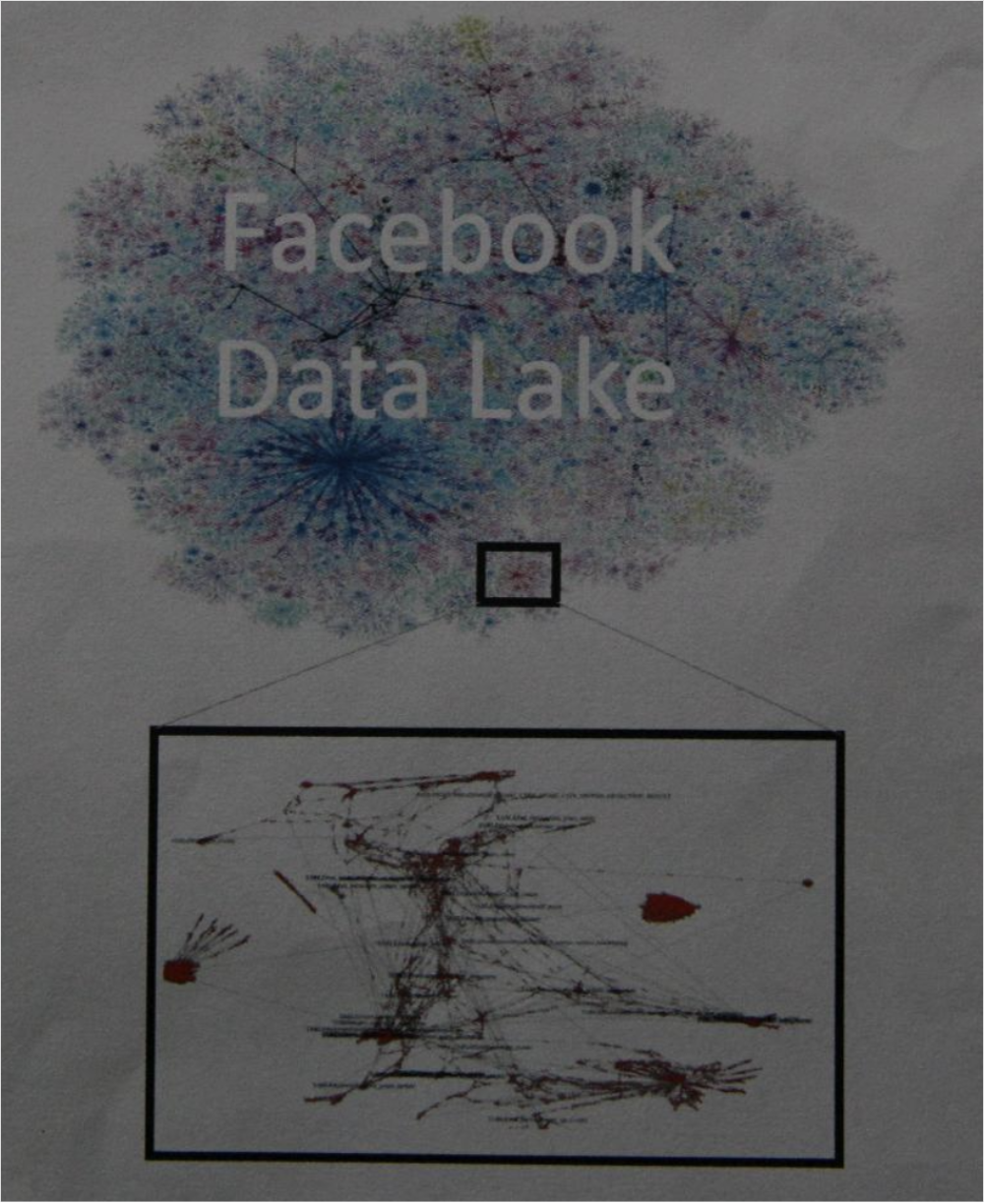

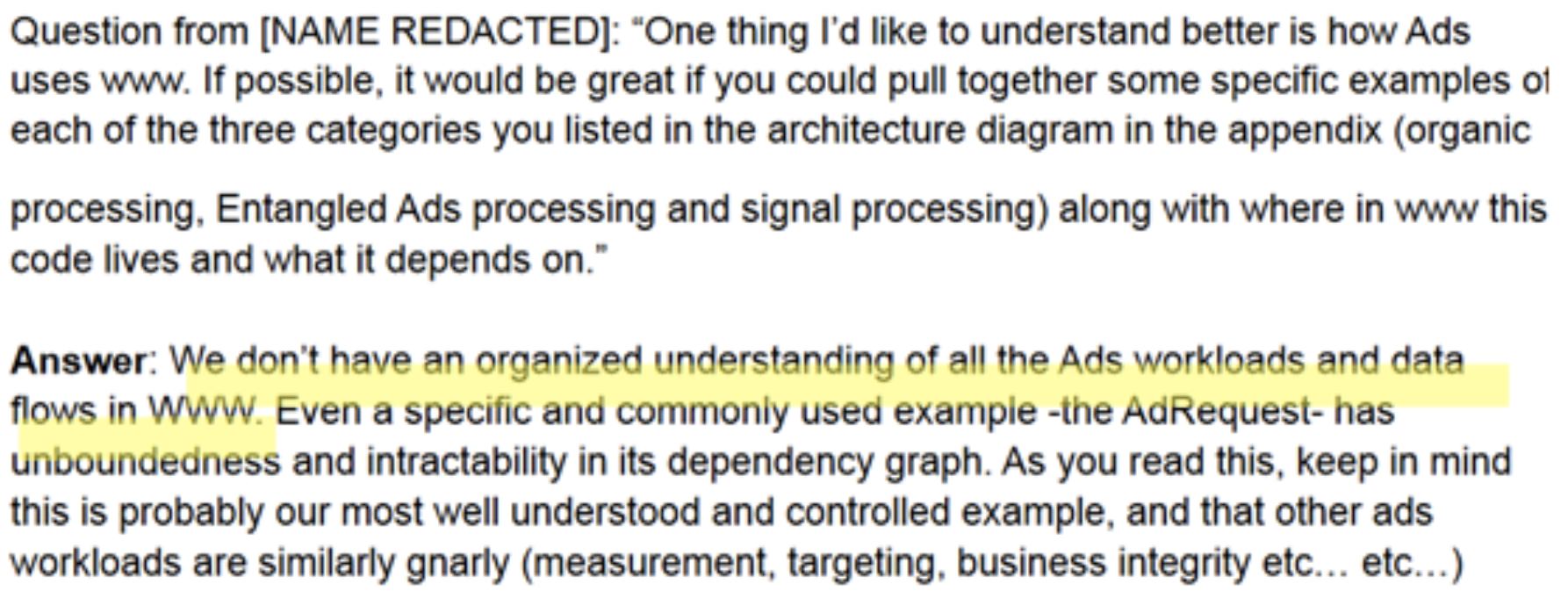

One of my favorite references for explaining why the world needs software safety labels is this story about two Facebook architects explaining how it’s virtually impossible for Facebook to know where user data is going. The complexity and dynamism of software is making it so it’s not a bounded system—and it’s never the same river twice. The story came out two years ago and I recently read the discovery document written in April 2021 and it is really good. This excerpt outlines the fundamental problem of the unknowability of Facebook software’s behavior:  And this:

And this:

The discovery document contains fascinating information on what Facebook must do to track personal data usage within its system [implement Curated Data Sources and a Purpose Policy Framework], and it’s a massive undertaking: 450-750 engineer years over three calendar years. And even that’s not enough. It also requires “heavy Ads refactoring and adoption work in warehouse.”

The discovery document contains fascinating information on what Facebook must do to track personal data usage within its system [implement Curated Data Sources and a Purpose Policy Framework], and it’s a massive undertaking: 450-750 engineer years over three calendar years. And even that’s not enough. It also requires “heavy Ads refactoring and adoption work in warehouse.”  Let’s go back to that “closed form system” described by the Facebook engineers. It comes from mathematics’ “closed-form expression”, describing an equation comprised of “constants, variables and a finite set of basic functions connected by arithmatic operations and function composition.”5 If we look at realtime bidding as one example of a programmed system, we see that it is necessarily dynamic and unbounded. The participants (buyers) in the realtime bidding network are dynamic; also the ad inventory itself is dynamic. Realtime bidding is, by design, never the same river twice. The system is not a closed form system. Machine learning (ML) is another example: virtually all of the ML technologies generating much recent hype are also not closed form systems by design. They are constantly changing based on the training set, based on ongoing learning, and based on dynamic rule-making.

Let’s go back to that “closed form system” described by the Facebook engineers. It comes from mathematics’ “closed-form expression”, describing an equation comprised of “constants, variables and a finite set of basic functions connected by arithmatic operations and function composition.”5 If we look at realtime bidding as one example of a programmed system, we see that it is necessarily dynamic and unbounded. The participants (buyers) in the realtime bidding network are dynamic; also the ad inventory itself is dynamic. Realtime bidding is, by design, never the same river twice. The system is not a closed form system. Machine learning (ML) is another example: virtually all of the ML technologies generating much recent hype are also not closed form systems by design. They are constantly changing based on the training set, based on ongoing learning, and based on dynamic rule-making.

2. Have We Agreed to Be Always Known and Tracked Online?

To summarize the situation: industry has developed techniques (distributed by design and company-centric) to interconnect and aggregate personal information such that we are always known and tracked online. As noted in the earlier mentioned research paper, there are at least $9T (as in trillion) worth of industries that want to know who we are and what we’re doing at all times. It’s unlikely that we can stop this financially motivated juggernaut of universal identification. So what’s to be done?

2.1 To Do List

- Consent is dead. It’s impossible and the more we pretend like it’s possible to have informed consent when it comes to the unbounded nature of software, the more we are lying to ourselves.

- Privacy policies protect companies but not the people who use technology. Know how you’ve consented into the worldwide web of commercial surveillance? It’s through this phrase found in many privacy policies: “…and we [may] share your data with our marketing partners.”

- We need more exposure of actual measured software behavior (ala ISL’s App Microscope: https://appmicroscope.org/app/1579/).

- One day, it will be possible for systems to generate machine-readable records of processing activities–a kind of passport stamp showing how your data was processed (used by first party, shared and used by third parties). This will be a landmark moment in empowering people through transparency of actual system behavior.

- Privacy policies protect companies but not the people who use technology. Know how you’ve consented into the worldwide web of commercial surveillance? It’s through this phrase found in many privacy policies: “…and we [may] share your data with our marketing partners.”

- Data broker regulation is inadequate.

- If a platform has your data, it should de facto have a first party relationship with you, and as such, you are entitled to all the proactive data governance rights allowed to you. In other words, nothing about me, without me. Data brokers aren’t and never have been just 3rd parties.

- Note that these data rights are unexercisable if people don’t know that they’re actually in a relationship with a particular platform. Thus, there also needs to be a requirements for these platforms to proactively notify all data subjects for which they hold information.

- Is the selling of personal information safe for humans and humankind? We’ve agreed as a society that certain things are sacrosanct and the selling of which unacceptably degrades and devalues them (such as votes, organs, children). We need to have a much deeper think about whether or not personal information should fall in that category.

- Are data broker laws effective in their current form? It seems clear to ISL that all actual data brokers are not currently registered in the states requiring registration.

- If a platform has your data, it should de facto have a first party relationship with you, and as such, you are entitled to all the proactive data governance rights allowed to you. In other words, nothing about me, without me. Data brokers aren’t and never have been just 3rd parties.

- Privacy and safety experts–and perhaps regulatory experts–need to get more aware of and involved in the two universal commercial identification standards (Unified ID 2.0 and European Unified ID) pronto.

- Identity resolution platforms and customer data platforms demand substantially more regulatory attention.

- Minimally, the massive troves of personal information are ripe for data breaches.

- Maximally, the public needs assurances that platforms that are amassing this data are held to accountability.

Footnotes:

- Note that ISL has not confirmed this.

- List of ISL designated data aggregators at the time of this writing: Adobe, Amazon, Apple, Google, Meta, Microsoft, and X.

- https://storage.courtlistener.com/recap/gov.uscourts.vaed.533508/gov.uscourts.vaed.533508.1132.2_1.pdf, page 7.

- See ISL paper on Identity Resolution and Customer Data Platforms for more information on universal identification schema.

- https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Closed-form_expression